Emergency meeting points:

- Gålö havsbad (lunch); 59°05'42"N 18°19'10"E

- Parking place Northern Gålö: 59°06'02"N 18°18'43"E

- Parking place Southern Gålö: 59°05'15"N 18°16'41"E

Social media outreach

Please use #IUFRO2024FutureForests when posting about your excursion experience

Contact to excursion organizers:

- Ida Wallin (SLU), ida.wallin@slu.se,

+46761353349 (WhatsApp & Signal) - Emma Holmström (SLU), emma.holmstrom@slu.se,

+4640415114 (WhatsApp) - Janina Priebe (Umeå University), janina.priebe@umu.se

+46768289323 (WhatsApp & Signal)

Times below are approximate and differ slightly depending on which group you belong to.

8 - 9 am

Bus transport & arrival to Gålö

9 - 12 am

Walk in the forest listening to presentations & discussing (incl. coffee & snack)

12 - 2 pm

Lunch at Gålö havsbad

2 - 5 pm

Walk in the forest listening to presentations & discussing (incl. coffee & snack)

5 - 6 pm

Transport back to Stockholmsmässan - latest arrival 18 o’clock

CAB

County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelsen)

CCF

Continuous Cover Forestry

SFA

Swedish Forest Agency (Skogsstyrelsen)

SLU

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (Sveriges Lantbruksuniversitet)

Broadl.

Broadleaves include mainly birch (Betula pendula/pubescens), aspen, rowan.

m3sk

Forest cubic meters, refers to the entire volume of the stem from the stump cut, including bark and top. Branches are not included.

m3fub

Cubic meters of solid mass under bark, refers to the actual volume of the stem excluding bark.

Noble B.

Noble broadleaves according to the Swedish Forestry Act include elm, ash, beech, hornbeam, oak, cherry, lime and maple.

Future Forests’ in-congress excursion focuses on people’s knowledge of forests and climate beyond the scientific knowledge produced in research organizations. We provide participants with a unique insight into how forest and climate knowledge is understood and interpreted by local actors in Sweden, including forest owners, women forest owner networks, tourism representatives, reindeer herders, hunters, forestry companies and environmental organizations. Together we discuss how local actors and citizens are key in the co-production of knowledge between society, science and academia. We deliberate upon policy barriers and opportunities for implementation of alternative forestry practices and how the Swedish “freedom with responsibility” model of governance affects this. Our focus is on how people’s knowledge of forests and climate can help to improve the monitoring of species’ response to climate change and to create more inclusive climate action by taking into consideration the knowledge dimensions of experiences, culture, emotions and facts.

Future Forests is a platform for interdisciplinary forest research and research communication. The platform is a collaboration between SLU, Umeå University and Skogforsk. It is one of SLU's four future platforms. Future Forests encompasses the importance of forests and forestry for the development of a biobased economy as well as climate adaptation and the various ecosystem services that forests offer. Participatory processes, where different groups' forestry perspectives are considered, are also included in the activities.

The Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) is a university with research, education and environmental assessment within the sciences for sustainable life. SLU’s activities span from genes and molecules to biodiversity, animal health, bioenergy and food supply. SLU is a public university funded through the budget for the Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure. In 2023, SLU had more than 4200 full-time students. SLU Swedish Species Information Centre (SLU Artdatabanken) accumulates, analyze and disseminates information concerning the species and habitats occurring in Sweden.

Umeå University (Sami: Ubmeje universitiähta) is a public research university located in Umeå, in the mid-northern region of Sweden. The university was founded in 1965 and is the fifth oldest within Sweden's present borders. As of 2015, Umeå University has over 36,000 registered students (16,000 full-time students). Internationally, the university is known for research relating to the genome of the poplar tree and the Norway Spruce.

The Swedish Forest Agency (SFA) is the national authority in charge of forest-related issues. Their main function is to promote the kind of management of Sweden's forests that enables the objectives of forest policy to be attained. The SFA is placed under the Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure.

The Archipelago Foundation (Skärgårdsstiftelsen) is the third largest landowner in Stockholm County and is responsible for preserving and developing large and close-to-city recreation areas for visitors since 1959. Their mission is to preserve the natural values and landscape of the Stockholm archipelago while promoting outdoor life, culture, tourism and more. The Archipelago Foundation has no owner and is governed by its statutes and the Foundation Act.

The County Administrative Board (CAB) of Stockholm is a governmental authority that serves the inhabitants of Stockholm County. All CABs in Sweden are an important link between the people and the municipal authorities on the one hand and the government, parliament and central authorities on the other hand. The CAB in Stockholm manages Gålö Nature reserve in close collaboration with the Archipelago foundation.

Gålö Havsbad is a camping site with a restaurant, basic amenities and the possibility of different outdoor activities including kayaking and pitch-and-putt. Tourists from Sweden and abroad gather here in summer, especially for the midsummer celebrations.

The Saami Council is a voluntary Saami organization (a non–governmental organization), with Saami member organizations in Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden. Since it was founded in 1956, the Saami Council has actively dealt with Saami policy tasks. For this reason, the Saami Council is one of the indigenous peoples’ organizations that have existed the longest.

Spillkråkan & Nordic Forest Women are both non-profit organizations for women who own forests and women in forest-owning families in Sweden and the Nordics respectively. They organize meetings, training courses, events and forestry trips in order to spread knowledge about sustainable forestry. They also participate in opinion formation to strengthen women's influence in the Swedish and Nordic forest industry.

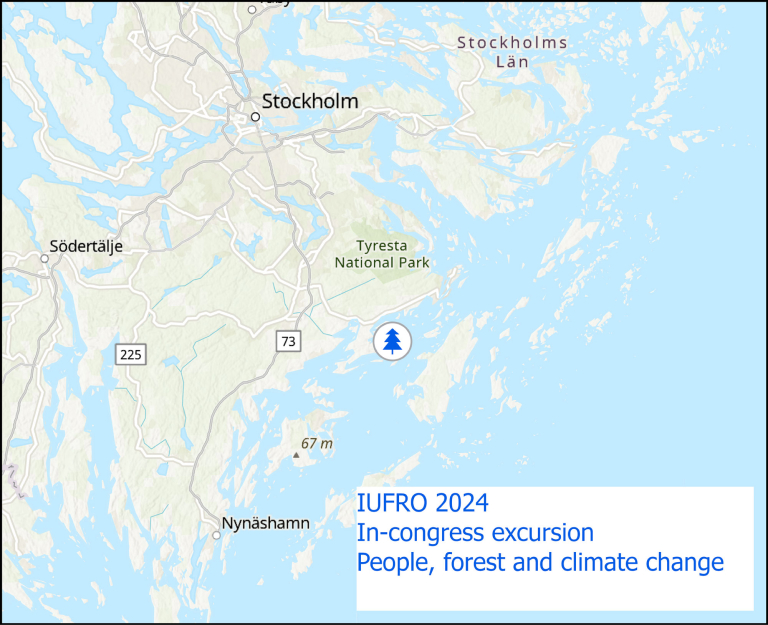

The excursion is taking place on Gålö Peninsula in Haninge Municipality, Stockholm County. Gålö Peninsula is located southeast of Stockholm. Known for its rugged beauty, Gålö boasts scenic trails for hiking and biking through the forest over cliffs made smooth by the ice some 10 000 years ago. Around 7000 years ago, Gålö started rising out of the sea after being suppressed by the ice. From the sandy beaches, you have a nice view of the Baltic Sea and surrounding islands. Gålö itself was an island until the 1940s when the narrow strait was filled up.

In 2006, Gålö Nature Reserve was established with an area of 3,835 hectares, including 1,750 hectares of land and a shoreline of about 50 kilometers of rocky and sandy beaches. Gålö has the longest sandy beach in the Stockholm archipelago – 480 meters long. The forest on Gålö mainly consists of managed Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Norway spruce (Picea abies). There are elements of deciduous trees, mainly oak (Quercus robur), along the edges towards cultivated land. There are also plantings of beech (Fagus sylvatica) as well as introduced species such as larch (Larix decidua) and silver fir (Abies alba). Higher-lying areas consist of rocky outcrops with pine forests on thin soils. These areas are less affected by forestry. Forests and wooded pastural areas with high nature values are found primarily in the northern Stegsholm area, around the southern rocky parts of Gålö, and on the surrounding islands. Today, most of the forest in Gålö Nature Reserve is to be managed with high standards of nature conservation and recreational considerations. Management decisions regarding the nature reserve are done by the Stockholm CAB in consultation with the landowner, the Archipelago Foundation.

Gålö is also a landscape of meadows and old agricultural lands. When turning off the main road and shortly before turning left towards Gålö havsbad one passes Stegholms farm with medieval ancestry. The landscape around Stegsholm farm is an old cultural landscape with pastures, oak groves, rocky areas and grazed beach meadows. Stegsholms’ oak meadows are designated as a Natura 2000 area.

There has been a military presence on the south-west corner of Gålö since 1942. The Gålö base was established here and remained in various forms until 1985. The area is still fenced off and not accessible to the public. The base is now the home harbor for the Navy's veteran flotilla. As part of their 'A Day in Paradise' program, the gates are opened to the public once a year.

Not far from Gålö Base is the Palmen Experimental Station, a secret military facility where the navy trained seals during World War II to search for enemy submarines underwater. The operation ended in April 1945. In 2018, an EU project called Footprints of Defense in the Archipelago opened the old seal station to the public.

In 1948, Gålö was acquired by the City of Stockholm. The idea behind the purchase was to offer people from Stockholm a large recreational area for leisure and holidays. Since 1998, most of Gålö has been owned and managed by the Archipelago Foundation, which leases out land for commercial activities and agriculture. With its sandy beaches and tranquil forests, Gålö Peninsula offers a serene escape from the hustle and bustle of city life and is much visited by the city folks.

Sources: Gålö Wikipedia page, Gålö Gärsar Heritage association website & CAB management plan

Lunch is served at Gålö havsbad and is catered by their restaurant. During the two-hour lunch break, we will get a taste of the traditional Swedish midsummer celebration at Gålö Havsbad. On the actual Midsummer night’s eve (Midsommarafton), around 3000 people visit Gålö Havsbad every year. This year they have kept some of the decorations for us. Here is a brief description of traditional Midsummer celebrations in Sweden:

Swedish Midsummer is a much beloved celebration marking the solstice and the longest day of the year. In modern times, Midsummer night’s eve is held on the Friday following the solstice and takes place between June 19th and 25th. It is a time when family and friends come together to enjoy the beginning of summer and the light evenings. A buffet of traditional foods and drinks is served coupled with singing, dancing and games. When the weather allows many try to sit outdoors for the dinner in the evening, but the beginning of Swedish summer can be surprisingly wet and chilly. A very classic midsummer celebration starts outdoors and then everyone must rush inside when the rain comes - while carrying all the food. The festivities typically include:

Maypole Dancing: A centerpiece of Midsummer celebrations, the maypole (midsommarstång) is decorated with birch leaves and wildflowers. Children of all ages gather around the maypole to dance and sing traditional songs that are often humoristic. One of the most popular songs is called The Small Frogs.

Folk music: The dancing around the maypole is often accompanied by live music and musicians play traditional folk music instruments such as violin and key harp (nyckelharpa).

Traditional Foods: The midsummer feast features an array of traditional Swedish delicacies, including many flavors of pickled herring, cured salmon, smoked salmon, potatoes with dill, sour cream, and chives. All finished off with a layered cake traditionally decorated with whipped cream and strawberries.

Drinking traditions: Sweden belongs to the vodka belt and on the Midsummer dinner table, there will be a small glass of traditional schnapps for those that want to go all-in. Some much-liked flavors and brands of schnapps include Skåne Aquavit, Bäska droppar, O.P. Anderson Aquavit, and Gammel Dansk. Very importantly, drinking schnapps at Midsummer is accompanied by singing. With your glasses raised, you sing a song in chorus and drink when the song ends by cheering and saying “SKÅL!” [skoːl].

Flower Crowns and Folk Costumes: It is common to wear flower crowns made from wildflowers or other seasonal blooms to the Midsummer festivities. Especially in some regions, the people wear traditional folk costumes.

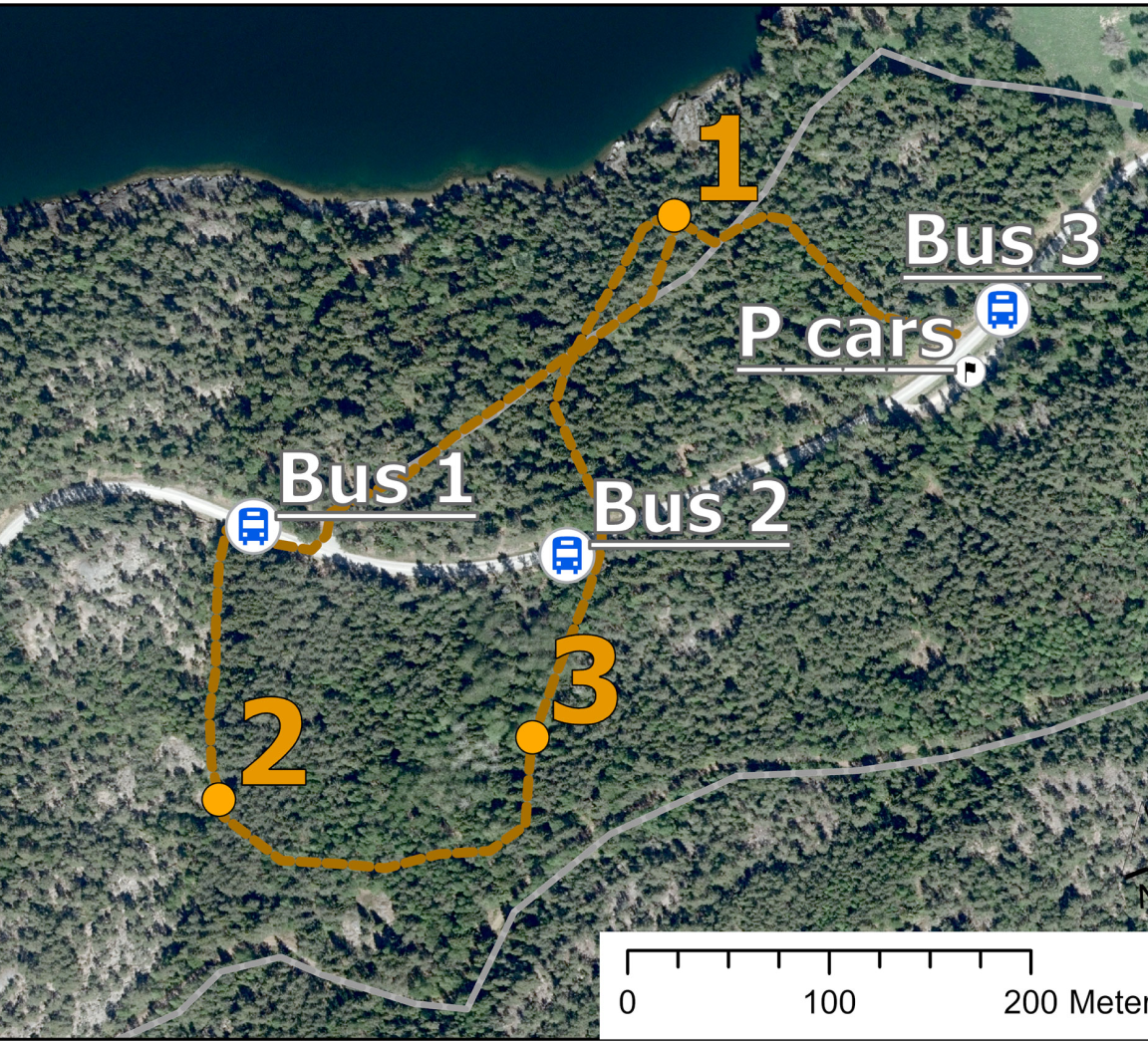

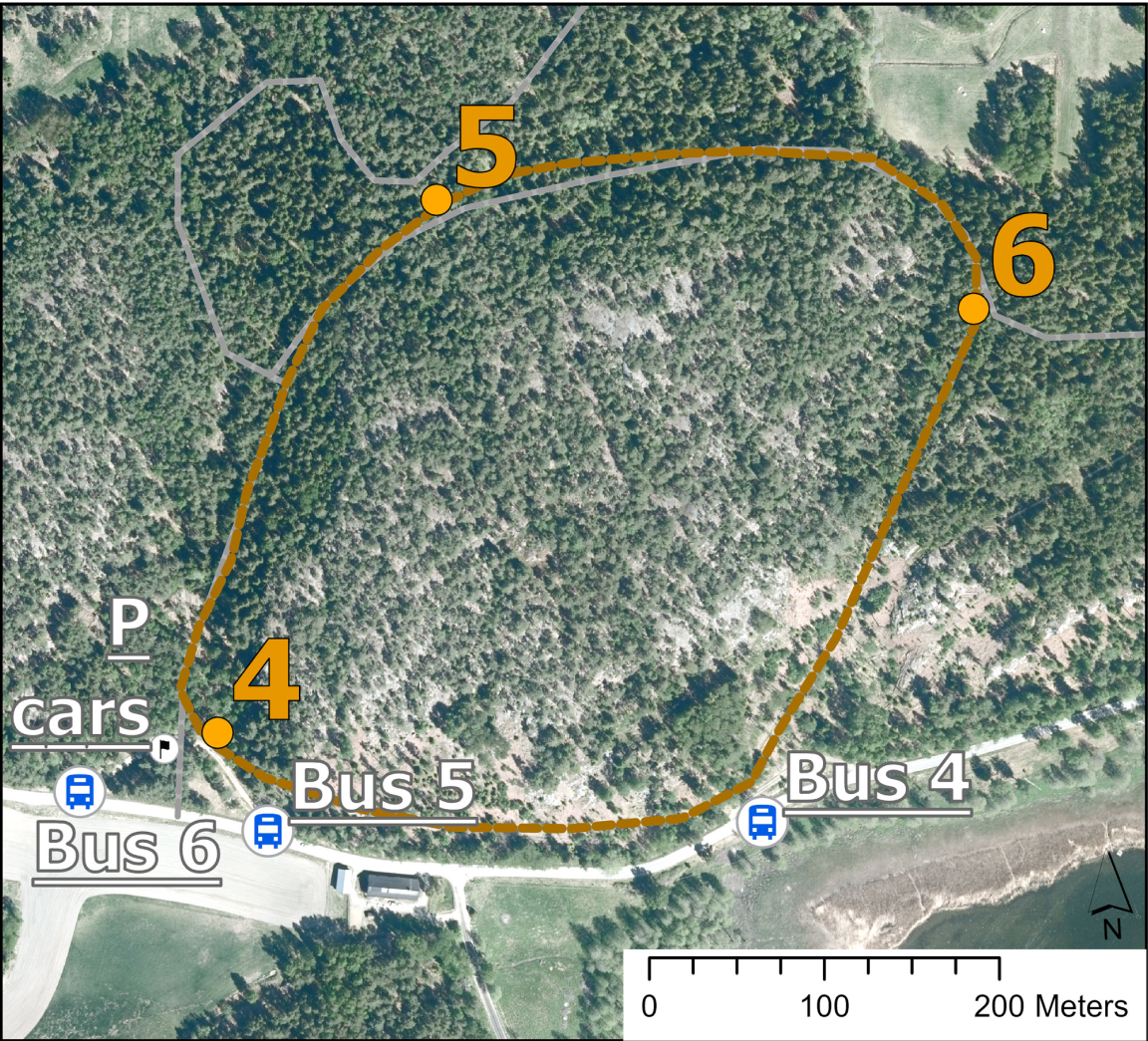

There are 12 presentations in total, and they are divided between 6 stations. Meaning two presentations at each station. The stations are distributed along two routes in the forest following small paths and roads, but also crossing the terrain. Participants are divided into two main groups that switch locations at lunchtime. In the Northern part of Gålö, you will walk through experimental forest stands where the Swedish Forest Agency did fellings in 2022 to demonstrate different clear-cut free practices. In the Southern part of the peninsula, you will walk through other parts of Gålö Nature Reserve and cross some stands damaged by storms and bark beetles.

Northern Gålö

1.a

Citizen science for monitoring biodiversity response to climate and land-use change

Mari Jönsson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

Mari Jönsson is an Associate Professor in biology at the Swedish Species Information Centre, SLU. Her research interests include citizen science, biodiversity, climate change, forest ecology and conservation.

Monitoring biodiversity response to climate and land-use change requires biological recordings that are large in spatial extent and spanning over long time periods. Sweden has a long legacy of nationwide biological recording, developed through the skills and commitment of volunteer participants in citizen science programs. In this talk, we examine the outcome of the online citizen science multi-taxon biodiversity platform Artportalen (www.artportalen.se) for monitoring of biodiversity response to climate change and forest land-use change in Sweden. We discuss the potential of these approaches for research, environmental monitoring and assessment, as well as their role in environmental governance and as a tool for education and outreach. In this latter perspective, we discuss the potential of citizen science for engaging society in biodiversity conservation and environmental issues.

1.b

Clearcut-free forestry and the archipelago´s recreational values

Jakob Bäckman, The Archipelago Foundation & Johannes Ackemo, Swedish Forest Agency

Jakob Bäckman is a forest manager at The Archipelago Foundation. Johannes Ackemo is a district forester at the Swedish Forest Agency working with forestry advice and supervision related to the Forestry Act and the Environmental Code.

Expectations and demands on forest ecosystem services are increasing. Values that are not so easy to put a price on, for example biological diversity, social values and health aspects require a changed perspective on the forest. Knowledge of how we can conduct a varied forestry is therefore important and needs to be developed. Since 2005, the Swedish Forest Agency has been tasked by the government to increase knowledge about clear-cut free forestry. The goal is to develop and convey knowledge about how clear-cut free forestry can be conducted related to production and environmental values as well as other general interests. To gain more knowledge, the Swedish Forest Agency works actively to establish demonstration areas. This talk focuses on the Swedish Forest Agency´s definition of clear-cut free forestry and the authority´s collaboration with the Archipelago Foundation in developing a demonstration area and why this is of interest for The Archipelago Foundation in their forest management.

2.a

Reindeer husbandry and forestry – from conflict to co-management?

Tim Horstkotte, Umeå University

Tim Horstkotte is a researcher at the Department of Ecology and Environmental Science, Umeå University. His research focuses on the impacts of land use change and climate change on boreal and arctic social-ecological systems.

Boreal forests in Northern Sweden are important grazing grounds for the indigenous Sámi livelihood of reindeer husbandry. At the same time, these forests are managed for the delivery of forest products. As climate change is altering the conditions for both forms of land use, finding common solutions for forest management to sustain functional grazing grounds and forest production becomes a challenging task. This talk focuses on these challenges how they could be addressed for a sustainable multiple-use of Swedish boreal forest.

2.b

The vital role of forests in Sámi livelihoods and tradition

Karin Nutti Pilflykt, The Saami Council

Karin Nutti Pilflykt is working as an advisor in one of the oldest still existing Indigenous Peoples Organizations in the world, the Saami Council. Karins primary focus lies in addressing forest and biodiversity related matters and Sámi indigenous rights. She is a forester by training and holds a master's degree in Land Use and Environmental Law.

The Saami people, Europe's only recognized Indigenous group, faces serious challenges. Climate change, a major concern along with other pressures like resource extraction and pollution, is putting the Sámi culture, livelihoods, and food security at risk. In light of these challenges, it is imperative to recognize and preserve the vital role of forests in Sápmi. This talk will highlight the importance of sustainable management practices, informed by indigenous knowledge and collaboration with Sami communities, which are essential for safeguarding both the integrity of the ecosystem and the resilience of Sámi livelihoods.

3.a

Green Infrastructure as a climate action tool?

Luis Andrés Guillén Alm, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

Luis Andrés Guillén Alm is a postdoctoral researcher on forest policy at Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, SLU and his research interests include forest advisory services to small-scale forest owners, forest governance and policy implementation, and the forest and water nexus.

Climate action encompass actions for ecosystem resilience and biodiversity conservation, e.g. increasing connectivity through green infrastructures. This talk focuses on empirical data on the implementation of forest green infrastructure, an approach that includes a landscape perspective to improve management of natural values through stakeholder collaboration. Practical challenges for forest green infrastructure implementation are present due to unclear mandates, organizational factors and the context of forest governance structures.

3.b

How the Nordic Forest Women Network can unpack embedded barriers for transition to sustainable forestry

Ingrid Stjernquist, Nordic Forest Women (NFW) & Stockholm University, Viktoria Byback, Spillkråkan, and Helena Geijer, NFW

Ingrid Stjernquist is the Swedish representative at the Board of NFW and Senior researcher in systems analysis and forest ecology at Stockholm University. Viktoria Byback is chairperson of Spillkråkan, an association for women forest owners, Helena Geijer is a representative of NFW, a Nordic network for women forest owners.

Sustainable forest management for bioeconomy transition is a complex dynamic system including feedbacks. Structural factors and social components in combination have to align if entrepreneurs in the forest sector are to succeed. Systems thinking and a gender perspective can both contribute to unpacking embedded barriers and lead to innovation. The talk focuses on a sustainability transition with a gender-oriented, bottom-up perspective using women’s more diverse and innovative forest management as role models. NSK and the Swedish network Spillkråkan recognize the importance of the forest in relationship to environment, climate change, economy and equality and build on the differences between member countries and forest zones to strengthen the network by creating a learning organization and educational network to empower women’s decision-making capacity.

Southern Gålö

4.a

Improving future studies - Combining scientific and local knowledge in scenario analysis

Isabella Hallberg-Sramek, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

Isabella Hallberg-Sramek is a researcher at the Department of Forest Resource Management, SLU and a visiting postdoctoral researcher at the Forest and Nature Conservation Policy group at Wageningen University and Research (WUR). Her research focuses on understanding the relations between people and forests and their potential impacts on future forests.

Future studies in forest research usually rely on science-based modeling approaches, while other types of scenario analysis have been less common. In a recent study, we developed, modeled and evaluated future scenarios together with forest stakeholders in order to combine both scientific and local knowledge in the evaluation of future scenarios. This talk will focus on what we learnt from this process and how we can improve future studies.

4.b

Transdisciplinary - the spectrum of knowledge

Janina Priebe, Umeå University

Janina Priebe is an associate professor in history of science and ideas at Umeå University and focusses on sustainability issues, environmental history and natural resource development from a historical perspective.

Holistic views of sustainability embrace integrated approaches that recognize domains such as meaning, behavior, culture, and systems as essential to knowledge. This talk focuses on an analysis of empirical data from a collaborative process with Swedish forest stakeholders that revealed a nuanced relationship between knowledge about forests and climate change. The interplay of meaning-making, cultural frameworks, and techno-scientific knowledge underscores the importance of a comprehensive understanding in addressing climate and sustainability issues.

5.a

Governing Swedish forests on the Route to Paris

Auvikki de Boon, Umeå University

Auvikki de Boon is a postdoctoral fellow at the department of Political Science, Umeå University. Her research interests include the governance of sustainability transitions, with a particular focus on questions of justice, legitimacy, social acceptability, adaptive capacity, and the role of policy design and implementation.

Sweden is the EU country with the highest forest cover and needs to deliver the largest carbon sink in the EU according to the LULUCF regulation. This talk focusses on how EU’s ambitions to fulfil the Paris Agreement commitments are translated into the Swedish national context. Special attention is given to how the idea of a ‘just transition’ is operationalized both at the EU and Swedish national level.

5.b

Socio-economic indicators to the national environmental quality objectives applied to the Swedish forest sector

Anniina Kietäväinen, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

Anniina Kietäväinen is a Ph.D. student at the Department of Forest Economics, SLU.

Sweden has adopted Environmental Quality Objectives (EQOs) to achieve a clean and healthy environment for future generations. Selected socio-economic indicators adapted from the Montréal Process for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate and Boreal Forests (MP) were identified and assessed over period of 20 years (2000-2020) in order to examine Swedish forest sector trends of direct relevance to the EQOs.

6.a

Increased local community agency in the face of climate change induced wildfire

Jenny Ingridsdotter, Umeå University

Jenny Ingridsdotter is an associate professor in Ethnology at Umeå University and focuses on issues related to power and geographies, such as migration, colonial structures and the studies of places through an ethnographic perspective.

The wildfires in Swedish forest in 2018 affected 25 000 hectares of forest. This talk draws upon an ethnographic study on three local communities that were particularly affected by these wildfires. The study focused on how local resources were mobilized in order to cope with the crisis and what the crisis led to in terms of strategies and awareness of sustainable development in the future.

6.b

Climate change adaptation - concepts and measures

Carola Häggström & Kristina Blennow, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU)

Carola Häggström is a researcher in work science at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and focusses on forestry worker’s interaction and well-being from a cognitive perspective. Kristina Blennow is a professor in Landscape Planning directed towards Landscape Analysis, in particular risk analysis and climate change.

Forestry professionals’ management choices and methods show great impact of current and future forests. This talk focuses on an analysis of empirical data from an online survey with Swedish forest professionals that revealed their beliefs and practices with regards to adaptation of forests to a changing climate. The interplay of motivation, knowledge, and opportunities shapes the behavioural outcome serving an important role in the understanding and communication addressing climate change adaptation and stainability.

Forestry has been a vital part of Sweden's economy for centuries and is commonly described as the country’s green gold. The industrialization of forestry began in the mid-19th century when large-scale logging operations expanded rapidly toward northern Sweden, leading to significant changes of forest landscapes.

The experimental stands on Gålö have been initiated in response to the current debate in Sweden regarding the future of the dominant forest management model of rotational forest management with clearcuts. The experiments explore possible alternatives to the present management model.

In the current debate, many argue that we should not forget the lessons of the early industrial forestry and that non-clearcutting methods will lead to depleted forests. One core argument is that boreal forests have different natural dynamics than, for example, nemoral forests in Central Europe. The main barrier to a broad implementation of alternative forest management practices is the lack of experience and practical know-how related to these methods in the boreal system. This is where the experimental stands of the Swedish Forest Agency at Gålö comes in. They will contribute with empirical evidence and potentially lead to wider implementation on non-clearcut forestry practices depending on the results.

If you want to understand more of the historical context and current debate, we recommend you read any of the following publications that originate from different actors and scientists and give different perspectives on the topic:

Information about the current Swedish forest legislation is available in English on SFA’s website and a historical overview can be read in the working report Forestry legislation in Sweden by Jan-Erik Nylund (2009).

SFA’s overview of Swedish forest management over the centuries (2020): Forest management in Sweden Current practice and historical background

Report about the socioeconomic dimensions of Swedish forestry by Ronju Ahammad and Francisco X Aguilar, SLU Future Forests (2024): Socio-economic indicators for the assessment of sustainability in the Swedish forest sector, and linkages with the national environmental quality objectives

Report about sustainable forest management in the Boreal region from International Boreal Forest Research Association (IBFRA) and SFA (2021): Sustainable boreal forest management – challenges and opportunities for climate change mitigation

Report about forests’ role in climate transitions from the project Route to Paris and authored by Hannerz et al. (2024) Forestry and climate – what does science tell? English summary on pages 9-11.

The book Continuous Cover Forestry in Boreal Nordic Countries, eds. Paul Rautio, Johanna Routa, Emma Holmström, Cristian Kuehne, Jonas Cedergren, and Salja Huuskonen (Publisher: Springer), will be published in June 2024 and you can attend a workshop about the book in the Nordic pavilion on Tuesday 25/6 8:30-9:30 Sustainable Forestry: Exploring continuous cover forestry in Northern Europe.

You can also watch documentaries produced by Future Forests about current issues in Swedish forestry on Future Forests’ website.

Sweden’s rotation forest management with final fellings and clearcuts does not look the same everywhere and for all forest owners. The rotation period varies depending on factors such as tree species, site quality, and management objectives. Sweden includes a variety of climatic and ecological zones from arctic tundra in the North to the nemoral zone in the South. Rotation periods range from 50 to 120 years. Similarly, there is a North-to-South gradient in forest ownership due to history. This means that the size of clearcuts in Sweden varies from North to South as well. In southern Sweden, where the forest is mainly in the hands of small-scale family forest owners, clearcuts tend to be smaller. In contrast, in northern Sweden, where forests are to a larger extent owned by large-scale industrial companies, larger clear-cuts are more common. In 2021, the average clear-cut size in Sweden was 3.3 ha; in the most Northern parts of Sweden (Norra Norrland) 5.2 ha and in the most Southern part (Götaland) 2.3 ha [1] . Since a few decades, retention forestry has been implemented in Swedish legislation and certification standards, with retention of habitat elements after cuttings, such as riparian zones, standing dead trees, woody debris, and groups of standing trees. In 2021, the Swedish Forest Agency (SFA) introduced a definition of non-clearcut forestry:

Non-clearcut forestry on forest land intended for wood production implies that the forest is managed in such a way that the land always has a tree cover, without any larger clearcut areas. A clearcut is an area harvested for regeneration that is larger than 0.25 hectares and where there is an obligation to regenerate the forest.

The same year as the definition was published, ca. 728 500 ha forest land in Sweden was managed according to the definition of non-clearcut forestry [2] (2-3% of all forest land, 28 Mha).

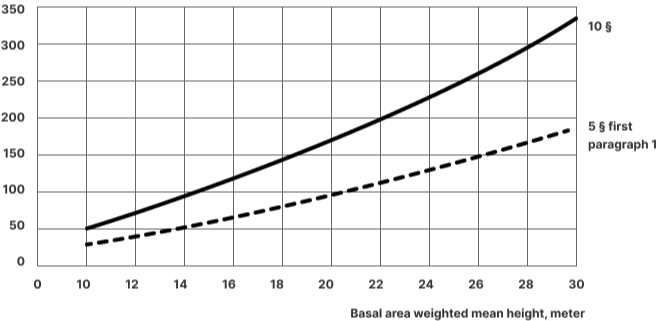

A reforestation obligation arises when the standing volume reaches the so called 5 § curve in the Forestry Act, see the final section of this information sheet “10. Fellings down to 5§ of the Swedish Forestry Act”.

[1] Swedish Forest Agency (2023) Felling statistics. Available from: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistik-efter-amne/avverkning/

[2] Swedish Forest Agency (2022). Forestry measures in 2021. Available from: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/statistik/statistikfaktablad/jo0301-statistikfaktablad-atgarder-i-skogsbruket-2021.pdf

During the excursion to Northern Gålö peninsula, we walk through the experimental stands planned by the Swedish Forest Agency (SFA). The project started in 2021 when the SFA informed the landowner, the Archipelago Foundation about different types of clearcut free treatments which led to the idea of creating a demonstration area. The project´s goal is to develop and convey knowledge and know-how about clearcut free forest management with focus on the production and environmental values as well as other general interests.

The experimental stands are located in the middle of a nature reserve that is managed jointly by the Archipelago Foundation and the County Administrative Board (CAB) of Stockholm. The active forest management of the area might seem at odds with the objective of nature conservation, but it is a common practice in Sweden. Nature reserves often serve the dual purpose of preserving outdoor recreation areas for the public and conservation. Such is the case also on Gålö where the purpose of the nature reserve is to preserve an archipelago area of great importance to outdoor recreation and at the same time preserve high nature values. The area´s historic farming landscape, valuable forests, and water areas as well as valuable flora and fauna are to be protected and cared for. Particularly valuable forest stands are exempted from forestry measures or are managed entirely according to conservation objectives. Other parts of the forest are managed more conventionally with enhanced biodiversity considerations and to keep it attractive for outdoor recreation.

Because of both nature conservation and outdoor recreation objectives, non-clearcut methods are of great interest in these areas and could be implemented where they are deemed suitable by The Archipelago Foundation. The future outcome from these experimental stands, in terms of regeneration success, stand development and conservation values, will provide decision-support for further implementation in similar forests and by other forest owners. Each area and treatment are described below and marked on the map 1-10. The information below comes from the SFA with some adjustments made by the Future Forests excursion organizers.

m3sk = Forest cubic meters, refers to the entire volume of the stem from the stump cut, including bark and top. Branches are not included. m3fub = Cubic meters of solid mass under bark, refers to the actual volume of the stem excluding bark. The conversion factor between the net felling in m3fub and the net felling in m3sk is estimated to be 1.188 [3].

[3] Swedish Forest Agency (2022) New conversion rate from m3fub to m3sk for harvest calculations. Available from: https://www.skogsstyrelsen.se/globalassets/om-oss/rapporter/rapporter-20222021202020192018/rapport-2022-16-nytt-omrakningstal-fran-m3fub-till-m3sk-for-avverkningsberakningar.pdf

Reference of what the forest conditions looked like on the northern side of the road before cuttings started in October 2022 in the neighboring stands.

| No management measure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Height (m) |

| 0.7 | 70 | Pine 45 Spruce 50 Broadl. [1] 05 Noble B. [3] 0 | 250 | 6.2 | 23 |

| No management measure | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 0.7 |

| Age (yrs) | 70 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 45 Spruce 50 Broadl. [1] 05 Noble B. [3] 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 250 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 6.2 |

| Height (m) | 23 |

Broadleaves include mainly birch (Betula pendula/pubescens), aspen, rowan, etc.. Noble broadleaves according to the Swedish Forestry Act include elm, ash, beech, hornbeam, oak, cherry, lime and maple.

Gap cuttings means that smaller gaps have been made in a stand with the intention of achieving natural regeneration within the gaps. According to the Swedish Forest Agency's definition, each gap may not exceed 0.25 hectares, but it is also possible to make them smaller depending on the conditions in the forest and the type of tree species to be regenerated. The method can be used for shade-tolerant, secondary tree species like spruce, but also pioneer tree species like pine and birch. On better soils with spruce, the gaps should be made smaller, while the gaps need to be larger on weaker (pine) soils.

As regeneration takes place within the gaps, they are enlarged until they "grow together" into an uneven-aged and somewhat uneven stand. If you want to rejuvenate a stand through gap felling, you should expect that around 3-4 felling operations are required and that it takes between 20-30 years before the entire stand has been processed.

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Height (m) | Stems/ha | Gap 1 (ha) | Gap 2 (ha) |

| 1.4 | 70-85 | Pine 46 Spruce 42 Broadl. 12 Noble B. 0 | 200 | 6.2 | 22 | 467 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 1.4 |

| Age (yrs) | 70-85 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 46 Spruce 42 Broadl. 12 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 200 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 6.2 |

| Height (m) | 22 |

| Stems/ha | 467 |

| Gap 1 (ha) | 0.15 |

| Gap 2 (ha) | 0.13 |

| Tree species | Tree species mixture (%) | Stems/ha (before) | Stems/ha (after) | Volume cut (m3sk) | Volume cut (m3fub) | Average stem volume (m3fub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 43 | 234 | 161 | 200 | 6.2 | 0.22 |

| Spruce | 40 | 149 | 111 | 39.4 | 2.3 | 0.61 |

| Broadleaves | 17 | 84 | 83 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 467 | 355 | 83.5 (30%) | 68.3 (30%) | 0.44 |

The aim of selective cuttings is to create stands or to maintain a fully layered forest structure, i.e. a forest with trees of all sizes from small seedlings to fully-grown trees. A fully layered forest has roughly the same appearance all the time and different development phases cannot be distinguished. Forests with the greatest potential for successful CCF are those dominated by tree species that prefer shade such as Norway spruce (Picea abies). Regeneration takes place through natural regeneration.

Successful selective cuttings are easier to achieve if the forest has a relatively high standing volume and timber extraction should take place at regular intervals, longer intervals on land with low productivity capacity and shorter intervals if productivity is high. The interval between cuttings is based on the timber harvest, something between 15-30 years. The harvest should not be greater than 30 percent; including cuttings for extraction roads (Swe. stickvägar) and in each cutting operation. According to CCF as volume based thinnings (Swe. volymblädning) it is the largest trees that are harvested.

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 1.3 | 85 | Pine 33 Spruce 51 Broadl. 16 Noble B. 0 | 244 | 5.5 | 23 | 399 | 48 | 15 |

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 1.3 |

| Age (yrs) | 85 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 33 Spruce 51 Broadl. 16 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 244 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 5.5 |

| Tree Height (m) | 23 |

| Stems/ha | 399 |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | 48 |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 15 |

| Tree species | Tree species mixture (%) | Stems/ha (before) | Stems/ha (after) | Volume cut (m3sk) | Volume cut (m3fub) | Average stem volume (m3fub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 39 | 103 | 99 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.23 |

| Spruce | 42 | 212 | 178 | 51.9 | 42.6 | 0.95 |

| Broadleaves | 19 | 84 | 84 | 0 | 0 | - |

| TOTAL | 100 | 399 | 161 | 53.3 (17%) | 43.7 (17%) | 0.44 |

Reference of what the forest condition looked like on the south side the road before cuttings were made in October 2022 in the surrounding stands.

| No management measure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Height (m) |

| 0.8 | 50 | Pine 72 Spruce 20 Broadl. [1] 05 Noble B. [4] 0 | 240 | 9 | 20 |

| No management measure | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 0.8 |

| Age (yrs) | 50 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 72 Spruce 20 Broadl. [1] 05 Noble B. [4] 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 240 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 9 |

| Height (m) | 20 |

Broadleaves include mainly birch (Betula pendula/pubescens), aspen, rowan, etc.. Noble broadleaves according to the Swedish Forestry Act include elm, ash, beech, hornbeam, oak, cherry, lime and maple.

For more light-demanding tree species such as pine, there is a need to apply methods that allow sufficient light to reach the ground for regeneration to take place. Therefore, selective cuttings are difficult to apply in pine dominated stands. Traditionally pine was naturally regenerated with retained seed trees, but today this method is usually replaced with planting. One suggested method to regenerate pine with a retained canopy is therefore to use a shelterwood and to return to natural regeneration instead of planting. The intention is also to keep the shelterwood for a longer time, compared to seed trees that should be removed as soon as the seedlings are established. The SFA has now defined when a natural regeneration with shelterwood can be considered as a clear-cut free method, which is based on a minimum expected volume considering stand height. The certification standards, however, don't necessarily share the same definitions. When there is an established regeneration, initial thinning can take place and when the average height of the regeneration is at least 2.5 m, the shelter trees can be harvested.

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 0.65 | 50 | Pine 66 Spruce 22 Broadl. 12 Noble B. 0 | 288 | 9 | 20 | 855 | 57-72 | 20-25 |

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 0.65 |

| Age (yrs) | 50 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 66 Spruce 22 Broadl. 12 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 288 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 9 |

| Tree Height (m) | 20 |

| Stems/ha | 855 |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | 57-72 |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 20-25 |

In this part of the stand, preparatory thinning has been carried out, to promote growth in the future seed trees, and the next measure will be to create a larger gap of about 0.20 hectares with the intention to be naturally regenerated with pine.

No separate data for this measure, it is included in point 7.

Here a preparatory thinning has been carried out to create a traditional seed tree stand with 50-150 stems per hectare. This is to show the difference between a maintained shelterwood and a seed tree stand.

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 1,31 |

| Age (yrs) | 50 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 71 Spruce 19 Broadl. 10 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 197 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 9 |

| Tree Height (m) | 19 |

| Stems/ha | 586 |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | 39-49 |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 20-25 |

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 1,31 | 50 | Pine 71 Spruce 19 Broadl. 10 Noble B. 0 | 197 | 9 | 19 | 586 | 39-49 | 20-25 |

| Tree species | Tree species mixture (%) | Stems/ha (before) | Stems/ha (after) | Volume cut (m3sk) | Volume cut (m3fub) | Average stem volume (m3fub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 76 | 440 | 283 | 77.3 | 63.39 | 0.20 |

| Spruce | 11 | 120 | 56 | 54.0 | 44.28 | 0.35 |

| Broadleaves | 13 | 104 | 74 | 7.4 | 6.1 | 0.09 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 644 | 413 | 138.7 (31%) | 43.7 (17%) | 0.23 |

Thinning has been carried out to promote various broadleaf trees such as aspen and birch. Here we plan to create a two-layered forest where the broadleaf trees act as shelterwood for the regeneration.

In this area, no measurement was carried out before the measure.

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 1.26 |

| Age (yrs) | 50 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 30 Spruce 30 Broadl. 40 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 180 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 7.2 |

| Tree Height (m) | - |

| Stems/ha | - |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | - |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 35 |

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 1.26 | 50 | Pine 30 Spruce 30 Broadl. 40 Noble B. 0 | 180 | 7.2 | - | - | - | 35 |

This area has been harvested to the minimum standing volume recommended. The Swedish Forestry Act regulates how much a forest owner is allowed to cut in a thinning. If the standing volume becomes lower than the regulation, this is considered a clearcut and must be reported to SFA as a final felling. These cuttings have been carried out in order to show what a forest looks like at the 10§ curve (see last page) before it must be notified for final felling. In this area, it was planned to leave about 10 % extra of the standing volume as a precautionary measure in case trees blow down.

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 0.9 |

| Age (yrs) | 70 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 35 Spruce 57 Broadl. 08 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 276 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 6.2 |

| Tree Height (m) | 22 |

| Stems/ha | 460 |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | 73 |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 30 |

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 0.9 | 70 | Pine 35 Spruce 57 Broadl. 08 Noble B. 0 | 276 | 6.2 | 22 | 460 | 73 | 30 |

| Tree species | Tree species mixture (%) | Stems/ha (before) | Stems/ha (after) | Volume cut (m3sk) | Volume cut (m3fub) | Average stem volume (m3fub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 43 | 188 | 181 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 0.46 |

| Spruce | 46 | 218 | 156 | 52.4 | 43 | 0.77 |

| Broadleaves | 10 | 54 | 52 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.07 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 460 | 389 | 55.9 (23%) | 45.9 (23%) | 0.72 |

This area has been harvested to the minimum standing volume recommended. The Swedish Forestry Act regulates how much a forest owner is allowed to cut in a thinning. If the standing volume becomes lower than the regulation, this is considered a clearcut and must be reported to the Agency. This area has been harvested down to the 5§ curve in the Forestry Act (see last page), the limit where the obligation to establish a new forest begins. This felling has been carried out in order to show what a forest looks like at the 5§ curve before the regeneration obligation normally occurs. In this area, it was planned to leave about 15 per cent extra of the timber stock as a precautionary measure in case trees are blown down.

| Before Cuttings | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (ha) | Age (yrs) | Tree species mixture (%) | Volume (m3sk/ha) | Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | Tree Height (m) | Stems/ha | Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | Planned volume harvest (%) |

| 0,55 | 80 | Pine 52 Spruce 41 Broadl. 07 Noble B. 0 | 256 | 5.5 | 23 | 451 | 76 | 54 |

| Before Cuttings | |

|---|---|

| Area (ha) | 0,55 |

| Age (yrs) | 80 |

| Tree species mixture (%) | Pine 52 Spruce 41 Broadl. 07 Noble B. 0 |

| Volume (m3sk/ha) | 256 |

| Incremental growth (m3sk/ha/yr) | 5.5 |

| Tree Height (m) | 23 |

| Stems/ha | 451 |

| Planned volume harvest (m3sk) | 76 |

| Planned volume harvest (%) | 54 |

| Tree species | Tree species mixture (%) | Stems/ha (before) | Stems/ha (after) | Volume cut (m3sk) | Volume cut (m3fub) | Average stem volume (m3fub) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | 79 | 207 | 142 | 27.8 | 22.8 | 0.63 |

| Spruce | 4 | 171 | 84 | 55.2 | 45.3 | 0.94 |

| Broadleaves | 17 | 73 | 73 | - | - | - |

| TOTAL | 100 | 451 | 298 | 83 (59%) | 68.1 (59%) | 0.81 |

Diagram from the Swedish Forest Agency's regulations and general advice in the Forestry Act. The curve for 10 § shows the minimum volume that the stand may have after felling. If the volume reaches the dotted curve (5 §), a reforestation obligation arises.

y-axis: Standing volume (m3 ha-1)

x-axis: Mean height (basal area weighted mean height, m)